On a JavaScript side project I’m working on, I ran across an an illustration of a few different refactorings, so I wanted to share a real-world example of them.

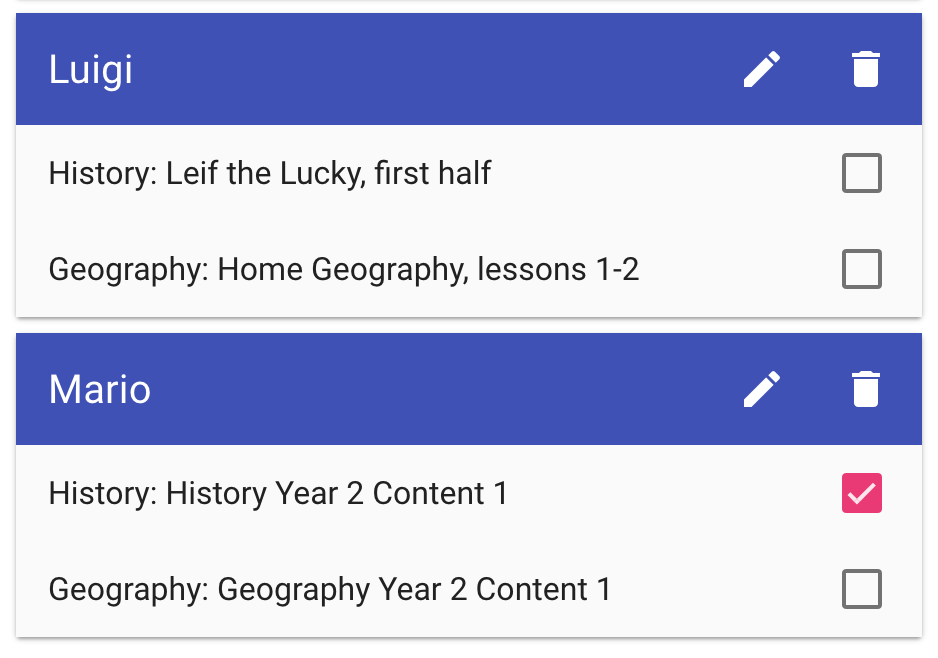

I’m working on an application for homeschooling parents to track the curriculum their child or children are going through. The view of a given day looks like this:

You can see that there can be multiple students, and for each one, there can be multiple content items they are studying.

There are actually two ways to configure content for a day: either standard or custom:

- The student can be assigned a customized set of

contentitems for the day. The relationship between astudentand acontentis called ascheduling. A student can have multipleschedulings for the day. Each one has acompletedproperty that can betrueorfalse. - OR, the student can be assigned a standard set of curriculum for a day. The standard day is called a

contentDay, which has multiplecontentitems. The record connecting thestudentandcontentDayis called astudentDay. In this case aschedulingrecord is created only when thecontentis complete, in which case thecompletedproperty is alwaystrue.

This is a pretty complex data structure! I needed to write a function to take those complex conditions and turn them into what you see in the screenshot.

To implement that, I wrote this function:

import matchesProperty from 'lodash/matchesProperty';

import property from 'lodash/property';

import sortBy from 'lodash/sortBy';

import uniq from 'lodash/uniq';

import uniqBy from 'lodash/uniqBy';

function schedulingsGroupedByStudent(day) {

const students = sortBy(

uniq([

...day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

...day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

const groups = students.map(student => {

const studentDay = day.studentDays.find(

matchesProperty('student.id', student.id),

);

const studentContents = studentDay?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

const contentSchedulingPairs = uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

...studentContents.map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

return {

student,

studentDay,

contentSchedulingPairs,

};

});

return groups;

}

A lot of us are used to writing functions this long and complex, including me. But as I look at it, it’s not very clear what’s going on. There is a lot of data processing happening in one place. So I would say this is an example of the Long Function code smell. I want to do some refactoring to it.

First I make sure it’s thoroughly covered by unit tests, so I can make changes to it with confidence. Next, I think about what approach to take.

Replace Function With Command

The easiest way to split up a large function is to use the Extract Function refactoring. But there is a lot of data flying around, so if I extracted functions in the same scope I would need to pass the same repeated arguments to them. Instead, I’ll use Replace Function with Command. This involves replacing a function with a class, and has the benefit of allowing multiple methods to access data via instance properties without needing to pass them as arguments. (Now, some JavaScript developers aren’t a fan of ECMAScript class syntax or behavior; in a part-two blog post I’ll perform the same refactoring, but using closure scope instead of classes, with some tradeoffs.)

To perform the Replace Function with Command refactoring, first I create a new class to hold the functionality:

class SchedulingGrouper {

}

Then I add a method to the class with the same parameters as the function:

class SchedulingGrouper {

groups(day) {

}

}

Then I copy the body of the old function into the new method without making any changes to it:

class SchedulingGrouper {

groups(day) {

const students = sortBy(

uniq([

...day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

...day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

const groups = students.map(student => {

const studentDay = day.studentDays.find(

matchesProperty('student.id', student.id),

);

const studentContents = studentDay?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

const contentSchedulingPairs = uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

...studentContents.map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

return {

student,

studentDay,

contentSchedulingPairs,

};

});

return groups;

}

}

So far, this code is not hooked up to anything. To hook it up, I replace the contents of the existing function with a call to instantiate a SchedulingGrouper and call its group method:

function schedulingsGroupedByStudent(day) {

return new SchedulingGrouper().groups(day);

}

I have the tests running in the background, so when I save the changes I see that the tests still pass.

This doesn’t get us a lot of benefit, though. Next we’ll change the day parameter into an instance property of the class; this will make it easier for new methods we create to access it.

First we add a constructor and take the day as an argument, assigning it to an instance property. For now we keep day as an argument to the group() method too:

class SchedulingGrouper {

constructor(day) {

this.day = day;

}

groups(day) {

//...

Next, we update the calling function to pass day when creating the new SchedulingGrouper:

function schedulingsGroupedByStudent(day) {

return new SchedulingGrouper(day).groups(day);

}

Next, we update group() to reference the this.day instance property instead of the day argument:

groups(day) {

const students = sortBy(

uniq([

- ...day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

- ...day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

+ ...this.day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

+ ...this.day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

const groups = students.map(student => {

- const studentDay = day.studentDays.find(

+ const studentDay = this.day.studentDays.find(

matchesProperty('student.id', student.id),

);

...

const contentSchedulingPairs = uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

- ...day.schedulings

+ ...this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

...

We save our changes and the tests still pass. Now we can safely remove the day parameter since it’s no longer used:

function schedulingsGroupedByStudent(day) {

- return new SchedulingGrouper(day).groups(day);

+ return new SchedulingGrouper(day).groups();

}

...

class SchedulingGrouper {

constructor(day) {

this.day = day;

}

- groups(day) {

+ groups() {

Extract Function

Now we’re ready to look through the groups() method to see other methods we could extract from it. The first chunk of code we see is this:

const students = sortBy(

uniq([

...this.day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

...this.day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

This is retrieving a list of unique students from two different parts of the data structure. This could be pulled out into another method using the Extract Function refactoring. To do this, first we create the new method:

students() {

}

Then we copy the statements over and return the result:

students() {

const students = sortBy(

uniq([

...this.day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

...this.day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

return students;

}

We replace the executing code with a call to this method:

groups() {

- const students = sortBy(

- uniq([

- ...this.day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

- ...this.day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

- ]),

- 'name',

- );

+ const students = this.students();

We save and the tests pass. Now we can simplify the students() method a bit. We can use the Inline Variable refactoring to return the result of sortBy() directly instead of assigning to a temp variable:

students() {

- const students = sortBy(

+ return sortBy(

uniq([

...this.day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

...this.day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

- return students;

}

We save and the tests pass.

Next, looking at the groups() method, there is only one place the students variable is used. So we can the Inline Variable refactoring again here, to replace the usage of that variable with the method call:

groups() {

- const students = this.students();

-

- const groups = students.map(student => {

+ const groups = this.students().map(student => {

Now we can see that the body of groups() is just one statement to create the groups variable, and then returning it. So we can inline that variable as well:

groups() {

- const groups = this.students().map(student => {

+ return this.students().map(student => {

...

});

-

- return groups;

}

This last change is an example of the cumulative power of refactoring. After you do one round of refactorings, more options for refactoring become visible to you.

Extract Student Functions

groups() is still pretty long, so let’s see what else we can do to split it up. Often it’s good to separate out iteration and what is performed during the iteration. In this case, for each student, what are we mapping to? We are mapping to the group for the student. So let’s extract a groupForStudent() method:

groups() {

return this.students().map(student => this.groupForStudent(student));

}

groupForStudent(student) {

const studentDay = this.day.studentDays.find(

matchesProperty('student.id', student.id),

);

const studentContents = studentDay?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

const contentSchedulingPairs = uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

...studentContents.map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

return {

student,

studentDay,

contentSchedulingPairs,

};

}

Looking at groupForStudent(), the temporary variables we’re using show that we compute three different values, then use those to return a result. Let’s split each of those computations out into its own function. First, studentDay():

groupForStudent(student) {

const studentDay = this.studentDay(student);

//...

}

studentDay(student) {

return this.day.studentDays.find(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id));

}

Note that studentDay is used for two things: it’s used directly in groupForStudent() as part of the return value, and it’s used to compute studentContents. To get the code well-factored, we’ll call studentDay() in both places; after some more refactoring, we may consider a performance improvement.

First we find the two places the studentDay variable is used and we inline the call to studentDay() at each: this will make future refactoring easier.

groupForStudent(student) {

- const studentDay = this.studentDay(student);

-

- const studentContents = studentDay?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

+ const studentContents = this.studentDay(student)?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

...

return {

student,

- studentDay,

+ studentDay: this.studentDay(student),

contentSchedulingPairs,

};

}

Next, we extract a studentContents() method:

studentContents(student) {

return this.studentDay(student)?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

}

And replace its implementation in groupForStudent():

groupForStudent(student) {

- const studentContents =

- this.studentDay(student)?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

+ const studentContents = this.studentContents(student);

We save and run the tests, and they pass. Next, we see that the studentContents variable is only referenced in one place, so we inline the call to the studentContents() method there:

groupForStudent(student) {

- const studentContents = this.studentContents(student);

-

const contentSchedulingPairs = uniqBy(

...

- ...studentContents.map(content => ({

+ ...this.studentContents(student).map(content => ({

Finally, we extract the contentSchedulingPairs variable to a method as well. We can go ahead and inline it right away:

groupForStudent(student) {

return {

student,

studentDay: this.studentDay(student),

contentSchedulingPairs: this.contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student),

};

}

contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student) {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

...this.studentContents(student).map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

Now groupForStudent() is a nice single level of abstraction. We can see at a glance that the group for a student is an object with three keys: the student, the student day, and the content scheduling pairs. If we want to dig into how the student day or content scheduling pairs are retrieved, we can look at the corresponding method.

contentSchedulingPairsForStudent still has some complexity, so it could be good to decompose further. But before we do, I’m starting to feel some hesitation.

Combine Functions into Class

We now have four methods in our class that take a student as an argument:

groupForStudent(student)studentDay(student)studentContents(student)contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student)

Avoiding duplicate argument passing is why we extracted a command object in the first place. But now we’re running into duplicate arguments again. This is because these functions all operate on a single student, rather than on all the students in the day. This is an evidence of lack of cohesion in the SchedulingGrouper class: one group of the methods all operate on a student, and another group do not.

Combine Functions Into Class is a refactoring that allows us to address this situation. We can take the methods that all take the same arguments, move them into a class, and then allow them to access those arguments as instance properties instead.

First, we create a StudentSchedulingGrouper class:

class StudentSchedulingGrouper {

}

Next, we copy the functions that take a student argument into it:

class StudentSchedulingGrouper {

groupForStudent(student) {

return {

student,

studentDay: this.studentDay(student),

contentSchedulingPairs: this.contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student),

};

}

studentDay(student) {

return this.day.studentDays.find(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id));

}

studentContents(student) {

return this.studentDay(student)?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

}

contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student) {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

...this.studentContents(student).map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

}

These functions are expecting a day instance property, so we go ahead and create a constructor to take it as an argument and assign that instance property:

class StudentSchedulingGrouper {

constructor(day) {

this.day = day;

}

Next, we replace the call to groupForStudent() in the original class to calling it on an instance of the new class:

groups() {

- return this.students().map(student => this.groupForStudent(student));

+ return this.students().map(student =>

+ new StudentSchedulingGrouper(this.day).groupForStudent(student),

+ );

}

We save and the tests pass.

Now we can remove the methods from SchedulingGrouper that we’ve copied to the other class, as they’re no longer called on the original class. We remove groupForStudent, studentDay, studentContents, and contentSchedulingPairsForStudent from SchedulingGrouper. We save and the tests pass.

Next, if we make the student an instance property of StudentSchedulingGrouper instead of an argument, we can fix the argument-passing problem. We add an additional constructor parameter to take in the student and we assign it to an instance property:

class StudentSchedulingGrouper {

constructor(day, student) {

this.day = day;

this.student = student;

}

Then, we update the call site to pass in the student there, leaving it as a method argument as well for now:

groups() {

return this.students().map(student =>

- new StudentSchedulingGrouper(this.day).groupForStudent(student),

+ new StudentSchedulingGrouper(this.day, student).groupForStudent(student),

);

}

We save and the tests pass. Now, one method at a time, we update them to use the student instance property instead of the argument. Since groupForStudent() takes the argument and forwards it along to children, we shouldn’t change groupForStudent() first as it will break the children; we should change the others first.

First, studentDay():

- studentDay(student) {

+ studentDay() {

- return this.day.studentDays.find(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id));

+ return this.day.studentDays.find(

+ matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id),

+ );

}

We save and confirm the tests pass, then move on to studentContents(). In this case it was just forwarding the student argument along to studentDay(), so we can just remove the incoming and outgoing argument:

- studentContents(student) {

+ studentContents() {

- return this.studentDay(student)?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

+ return this.studentDay()?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

}

Next, contentScheduingPairsForStudent:

- contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student) {

+ contentSchedulingPairsForStudent() {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.day.schedulings

- .filter(matchesProperty('student.id', student.id))

+ .filter(matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

- ...this.studentContents(student).map(content => ({

+ ...this.studentContents().map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

Now we can go back to groupForStudent() and remove the argument:

- groupForStudent(student) {

+ groupForStudent() {

return {

student: this.student,

- studentDay: this.studentDay(student),

+ studentDay: this.studentDay(),

- contentSchedulingPairs: this.contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(student),

+ contentSchedulingPairs: this.contentSchedulingPairsForStudent(),

};

}

We save and the tests pass. Now we can remove the student argument where groupForStudent() is called:

groups() {

return this.students().map(student =>

- new StudentSchedulingGrouper(this.day, student).groupForStudent(student),

+ new StudentSchedulingGrouper(this.day, student).groupForStudent(),

);

}

Rename Function

Before we proceed, let’s assess the names of these methods in their new location. A lot of them refer to a student, but the class name already tells us that it’s related to one student. So we can probably update these. We make the following renames, both at the method definition and call site, running the tests after each to ensure we haven’t broken anything:

groupForStudent()togroup()studentContents()tocontents()contentSchedulingPairsForStudent()tocontentSchedulingPairs()- Note that we leave

studentDay()as-is becausestudentDayis the name of the record type.

After these rename refactorings, notice how simple group() becomes:

group() {

return {

student: this.student,

studentDay: this.studentDay(),

contentSchedulingPairs: this.contentSchedulingPairs(),

};

}

We return a record with student, studentDay, and contentSchedulingPairs. student is an instance property, and the other two have methods with the same name as them that compute how they’re derived. (Now that they don’t take any arguments, we could even change these methods to getter methods and avoid having to use parens to call them. But as these aren’t as familiar to many JavaScript developers, I opted to avoid that.)

Now we can proceed with extracting more methods from contentSchedulingPairs(). Let’s look at it again:

contentSchedulingPairs() {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

})),

...this.contents().map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

There are two expressions we combine into one array, then remove the duplicates. What do those two expressions represent? Both are creating “content scheduling pair” records, which have a content property and a scheduling property. One is creating pairs from the schedulings, and the other is creating them from the contents. So let’s extract a method for each of these.

The first we can call contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings:

contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings() {

return this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

}));

}

We can call this in contentSchedulingPairs():

contentSchedulingPairs() {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

- ...this.day.schedulings

- .filter(matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id))

- .map(scheduling => ({

- content: scheduling.content,

- scheduling,

- })),

+ ...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings(),

...this.contents().map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

})),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

Now we can do the same for contentSchedulingPairsFromContents:

contentSchedulingPairsFromContents() {

return this.contents().map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

}));

}

contentSchedulingPairs() {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings(),

- ...this.contents().map(content => ({

- content,

- scheduling: null,

- })),

+ ...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromContents(),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

After this, contentSchedulingPairs is a nice single level of abstraction as well:

contentSchedulingPairs() {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings(),

...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromContents(),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

Review

Let’s take a look at the final code:

function schedulingsGroupedByStudent(day) {

return new SchedulingGrouper(day).groups();

}

class SchedulingGrouper {

constructor(day) {

this.day = day;

}

groups() {

return this.students().map(student =>

new StudentSchedulingGrouper(this.day, student).group(),

);

}

students() {

return sortBy(

uniq([

...this.day.studentDays.map(property('student')),

...this.day.schedulings.map(property('student')),

]),

'name',

);

}

}

class StudentSchedulingGrouper {

constructor(day, student) {

this.day = day;

this.student = student;

}

group() {

return {

student: this.student,

studentDay: this.studentDay(),

contentSchedulingPairs: this.contentSchedulingPairs(),

};

}

studentDay() {

return this.day.studentDays.find(

matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id),

);

}

contents() {

return this.studentDay()?.contentDay?.contents ?? [];

}

contentSchedulingPairs() {

return uniqBy(

[

// schedulings must come first so uniqBy prefers them

...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings(),

...this.contentSchedulingPairsFromContents(),

],

property('content.id'),

);

}

contentSchedulingPairsFromSchedulings() {

return this.day.schedulings

.filter(matchesProperty('student.id', this.student.id))

.map(scheduling => ({

content: scheduling.content,

scheduling,

}));

}

contentSchedulingPairsFromContents() {

return this.contents().map(content => ({

content,

scheduling: null,

}));

}

}

Now each of our methods is pretty simple; the longest one is eight lines, including a comment. Our tests are still passing, so we know it works. Let’s see if this helps us understand our code:

- Our externally-facing API is still the

schedulingsGroupedByStudent()function. - That function now creates a

SchedulingGrouperinstance and delegates to itsgroups()method. - The

groups()method gets an array ofstudents()and, for each one, it uses theStudentSchedulingGrouperto get thegroup()for that student. - The

group()method ofStudentSchedulingGrouperreturns an object with three fields:student,studentDay, andcontentSchedulingPairs. Of the three,contentSchedulingPairsis the most interesting. contentSchedulingPairs()gets pairs from two sources: from schedulings and from contents. Then it removes any duplicates.- The way pairs are derived from schedulings and contents is defined in two different methods.

This a nice stepwise way we can understand the functionality here. We don’t need to read a whole long function and try to understand the intent of each step. We have created methods that give names to each concept. And because we’re using class instances instead of standalone functions, we don’t need to pass a lot of arguments to the methods; they have access to instance properties and to call other methods to get the information they need.

As I mentioned before, you don’t need to use classes to decompose your code in this way; you can also do it using JavaScript scope and nested functions. In my next post we’ll go through this refactoring sequence again using that alternative approach.