The last few months have been my first opportunity to do automated testing at my full-time job. As I’ve been trying to get the hang of it, my biggest question has been how many of each type to test to write: how many unit, integration, and acceptance tests. Turns out Folks Got Opinions™ on this! As I researched, I found at least four different approaches to testing, and they each provide different answers to a number of questions I had:

- What are the different test types for?

- How much do I test?

- What process do I go through to write tests?

- How do I use test doubles?

- What do I check for in my tests?

But it turns out these approaches also answered some bigger-picture questions I wasn’t expecting:

- How do I deal with change in my application?

- What even is good code?

I wanted to share what I found, hoping it will help you learn some new approaches to try, whether you’re a testing newbie like me or a seasoned veteran. And as a bonus, I have a crazy theory to share: each approach to testing is tailor-made to guide you towards a certain kind of architecture. So, if you try to use a testing approach for an architecture it’s not a good fit for, you’re gonna have a bad time.

One quick note: there aren’t hard boundaries between these types of testing. Don’t think of it as though you have to pick one and use it all the time. Think of them as tools you can apply in different situations as they fit best.

First, since terms for categories of tests are used in so many different ways, here’s how I’ll use them in this post:

- Acceptance test: tests the whole system from the outside (i.e. web user interface).

- Integration test: tests an object connected to other objects and/or external systems (i.e. the database).

- Unit test: tests an object in isolation from any other objects.

- “Unit” test: when I am being sarcastic about Kent Beck saying “unit test” to refer to what the industry considers an integration test. More on this in a minute!

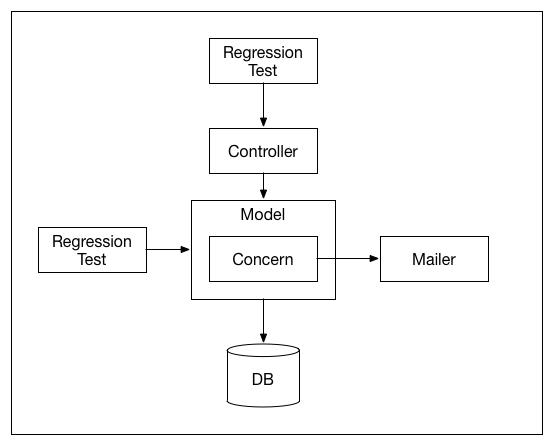

Test Approach #1: Whatever it is DHH does.

(Maybe “Regression Testing”?)

You may have heard about the “TDD is Dead” firestorm that DHH, the creator of Rails, kicked off in 2014. DHH is nothing if not opinionated, and these opinions extend to Test-Driven Development. Reacting to what he perceived as inherent problems with TDD, DHH proposed returning to a simpler test-after approach, focusing only on regression testing.

Resources

- “TDD is Dead”, the blog post that started it all.

- “Writing Software”, a conference keynote that DHH gave around the same time as the blog post.

- “Is TDD Dead?”, a series of recorded Google Hangouts between DHH, Kent Beck, and Martin Fowler where they discussed which of DHH’s points they do and don’t agree on.

- What are the different test types for? Acceptance and integration tests are for regression testing. Unit tests don’t provide any value: they don’t really test that your application works. Furthermore, changing your code to be easy to unit test makes it more difficult to read and understand, leading to “test-induced design damage.”

- How much should I test? Test only what’s valuable. Maybe the most common use cases of your app, or what makes you money. You don’t need to test every feature of your app.

- What process do I go through to write tests? Write the code, test it manually, then optionally write regression tests.

- How do I use test doubles? Don’t. Always use your real, connected production code. This ensures you’re testing real behavior.

- What do I check for in my tests? Mostly check for rendered page content or database entries. Integration tests that access objects will also check return values.

- How do I deal with change? Refactoring is de-emphasized. Most of what DHH talks about is adding new features to your app, not about restructuring your code to make it more flexible as your application grows. Also, he discourages code reuse, such as making your business logic accessible from the command line or web services. [Is TDD Dead?]

- What even is good code? Simple, readable code. Small classes and methods are no advantage if they make it harder to read through and understand the entirety of what a user request does. I won’t say definitively that he’s advocating procedural coding, but he’s much closer to it than the other approaches.

Criticisms

- There are a lot of dependencies between classes. They’re hard-coded to use each other, and can end up with a lot of coupling between one another. Even if you don’t Need to reuse code, this can make it hard to understand for debugging and adding features.

- Because of this coupling, it’s difficult to follow this approach as apps grow in size. Defects can go up and development speed can go down.

- It’s concerning to me that there’s no mention of refactoring, suggesting that when you run into difficulties doing it you may be on your own figuring out how to handle them. Regression tests certainly do provide some protection and flexibility for it. But when the tests don’t fully cover the behavior of the system, refactoring can be risky.

Test Approach #2: Classical TDD

Test-Driven Development originated with Kent Beck. After the development of Mockist TDD as an offshoot, the original formulation began to be referred to as Classical TDD or the Detroit School of TDD.

Resources

- Test-Driven Development: By Example, an early book where Kent Beck most thoroughly lays out his view.

- “Mocks Aren’t Stubs”, an extended blog post where Martin Fowler contrasts Classical and Mockist TDD.

- “Classicist and Mockist TDD”, a podcast episode that does the same.

- “Is TDD Dead?” panels.

- “TDD: Where Did It All Go Wrong”, a conference talk where Ian Cooper contrasts correct and incorrect applications of Classical TDD.

- What are the different test types for? “Unit” tests are for driving design…for sufficiently large definitions of “unit.” Beck admits that his usage of the term “unit” is different from most developers before him—and that’s remained true since then. It’s closer to what others mean when they say “integration testing”: testing several classes working together. [AGR]

- How much should I test? Test everything once and only once. You don’t write a line of production code until you first have a test that fails without that line. I say test everything only once because duplicate test coverage is discouraged. If you refactor a class to extract another new class, the new class is already covered by your existing test: don’t write an additional test for it. [AGR]

- What process do I go through to write tests? “Red, green, refactor.” First write just enough of a test to fail (making your test output red). Then write just enough production code to make the test pass (green). Then refactor to improve the code—especially by removing duplication.

- How do I use test doubles? Only when necessary; test classes against their real collaborators as much as you can. Use stubs only when the real collaborators are difficult to work with, such as connection to third-party or asynchronous services. [MAS]

- What do I check for in my tests? Check state, internal and external. For example, you might send a message to one object then check a value three objects away. You might also have to expose some internal properties of an object just for testing.

- How do I deal with change? Refactor the class’s implementation, which includes its collaborators that aren’t directly accessed from the outside. Because the collaborators aren’t tested directly (see question 2), it’s easy to change them and ensure they still return the same result overall.

- What even is good code? A black box with well-defined external functionality.

Criticisms

- When testing state, sometimes you have to expose internal variables only for the sake of testing. This was one of the main motivations for the creation of the third test approach below. However, Classical TDD practitioners say this doesn’t cause a big problem. [CAM]

- The methodology doesn’t exert pressure on you to refactor, so that step can often be minimized. Put practitioners say that as your design skills grow, you do this more. [FITDD]

- Extracting objects is a painful process. [FITDD]

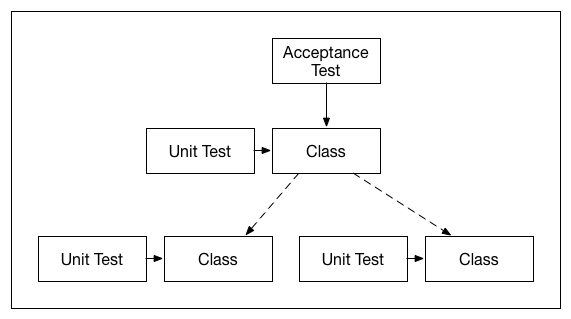

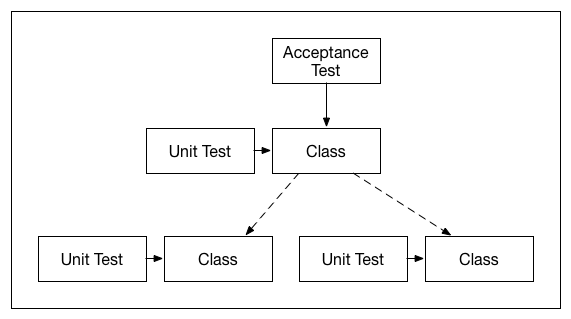

Test Approach #3: Mockist TDD

This approach started in London’s XP Tuesdays meetup in response to what they perceived to be problems with Classical TDD, especially the frequent need to expose internal object state for testing. It’s sometimes referred to as the London School of TDD, Isolation Testing, or Outside-In Testing. It’s closely related to Behavior-Driven Development (BDD), although BDD has a larger scope involving customer interaction and feature prioritization.

Resources

- Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests, considered by many to be the foundational articulation of Mockist TDD.

- The RSpec Book, an introduction to BDD, Mockist TDD, and Rails-specific tools for doing it.

- “Mocks Aren’t Stubs” blog post.

- “Classicist and Mockist TDD” podcast episode.

- “Test Isolation is About Avoiding Mocks”, a blog post about the criticism of “too many mocks.”

- “Outside-in TDD and Dependency Injection in Rails”, a podcast episode that mentions the issue of class extraction and test-after development.

- What are the different test types for? Acceptance and unit tests are both for driving your design, not just unit tests as in Classical TDD. Acceptance tests are also for catching regressions—unit tests are not. [GOOS]

- How much should I test? You test everything at both the acceptance and unit level, since you only write unit tests and production code when an acceptance test drives you to them. [RB]

- What process do I go through to write tests? Do two red-green-refactor circles, one at acceptance-level and the other at unit-level. Write an acceptance test that defines the user-facing behavior needed. When it fails and you need to write production code to fix it, first write a unit test for the class you need, and only then then write the class. Continue to write unit tests and production classes until the acceptance test passes. [RB]

- How do I use test doubles? Stub or mock all collaborators. Mockists use the traditional definition of “unit test”: a class that’s tested by itself without any real collaborators, frameworks, or external services.

- What do I check for in my tests? Check behavior, not state. Mockist testing emphasizes the Tell-Don’t-Ask principle, which means that classes usually issue commands to other classes, rather then asking for data and then deciding what to do with it. Mocks provide the easiest way to verify that those messages are sent. When there are return values you check those directly.

- How do I deal with change? The internals of a class can be refactored. When changes across multiple classes are needed, the mocks in tests discourage you from changing interfaces too quickly. If classes can be reused to provide the newly-desired behavior, that’s preferable.

- What even is good code? Small, reusable components. By isolation testing including outgoing messages, this approach encourages you to think about how objects collaborate, which leads to more consistency between interfaces and easier reuse. [GOOS]

Criticisms

- Mocks are not actually testing that the system works. However, that’s not the purpose of unit tests: they’re for driving your design. Regression testing is what your acceptance tests are for.

- There can be a tendency to have three or more levels of mocks, making them very hard to read. But this is exactly the design feedback unit tests are supposed to provide, simplifying your code by applying the Tell-Don’t-Ask principle to reduce the number of mocks needed. [AM]

- Mocks couple you to the implementation of your classes, making it impossible to refactor without changing tests. But if you want reusable components, outgoing messages are the interface. The implementation is what’s in the method and any private methods, not what’s an outgoing message. It’s true that this introduces some rigidity, but it’s a necessary tradeoff to be able to have reusable components.

- Extracting a class during refactoring and then adding tests is test-after development, which loses the benefits of TDD. But you can first write the new class as an inner class, then TDD it as you pull it out one bit at a time [OITDD]

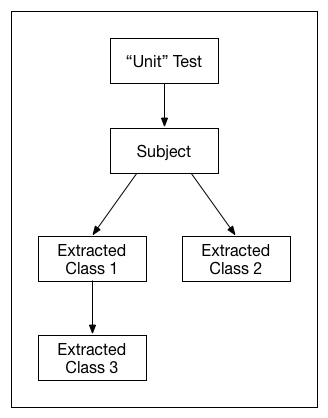

Test Approach #4: Discovery Testing

Discovery Testing is a response to both Classical and Mockist TDD and the perceived difficulties that both present in terms of refactoring. Justin Searls of Test Double is the main proponent.

Resources

- “The Failures of Intro to TDD”, the main blog post that lays out this view.

- “Tests’ Influence on Design”, an article with more detail.

- “The Testing Pyramid”, an illustration of the roles of the different test types.

- What are the different test types for? Unit tests are for driving your design and acceptance tests are for regression. [TP]

- How much should I test? Test-drive everything at the unit level, then test at the acceptance level to catch regressions.

- What process do I go through to write tests? Red, green, then…implement the collaborators you mocked. What this means is that you decompose the problem into collaborators from the start, instead of refactoring after the fact as in other TDD approaches. [FITDD]

- How do I use test doubles? Stub or mock all collaborators.

- What do I check for in my tests? Check behavior, just like in Isolation Testing.

- How do I deal with change? Throw out and rewrite a subtree of your classes. These classes are intended to be so small that it’s easier to rewrite them than refactor them. [FITDD]

- What even is good code? A tree of tiny, disposable classes. [FITDD]

I haven’t found any responses to Discovery Testing online, but here are the questions I have about it:

- Does disposable code work for complex features? Even if each class is tiny, one feature might be implemented with dozens of classes that you’d have to throw out if the feature changed at a high level.

- Is code reuse never worth the cost?

- Do you always know the right way to decompose your problem at first?

So how do you decide what testing approach to take? I would suggest that the better question is, what kind of system do you want to create?

- Refactorable black boxes?

- Pluggable components?

- Disposable subtrees?

- …Literature? I guess?? I’m not sure what to call what DHH advocates!

The answer is It Depends™. On a number of things:

- On your personal wiring.

- On your experience level with each testing style.

- On your experience level in software design.

- On your experience level in the problem domain.

- On team and organization structure.

- On the needs and constraints of the system.

- On your project working style: waterfall vs. iterative.

But you want to make sure to choose the right testing tool for the kind of system you want to create; otherwise you’ll chafe at the direction the tests are steering you. I think this is the cause of a lot of people’s frustration with certain testing styles.

- If you want to do black-box refactoring but you use Isolation Testing, you’ll get frustrated that you have to change mocks every time you refactor.

- If you want “simple, readable code” the way DHH defines it but you use any TDD approach, you’ll resent the small objects the tests lead you to.

- If you want to do a lot of component reuse but you use Classical TDD, it won’t give you the design pressure to help you with that.

What’s your personal testing approach? Does it match up with the kind of system you’re trying to create? Did you get any ideas for new techniques you might want to try?

Thanks to the folks at Big Nerd Ranch for listening to this content in talk form and providing feedback!