In our software development process we want more value: more useful software delivered. The first technique we tend to reach for is to add more developers to the team. How well does this work?

There are a lot of factors involved, so let’s think through it for one set of assumptions:

- We’re talking about multiple developers on a single codebase where any developer can work in any area of the code. No siloing by programming language or feature.

- All developers on the team have the same skill level and are fully onboarded onto the project.

- Developers create a feature branch working solo, then open a PR, which is reviewed by one other developer. All developers perform code reviews.

In this scenario, then the amount of useful code delivered increases linearly with the number of developers. Two developers deliver two units of code, three deliver three, etc. The amount of time needed for PR review doesn’t increase, because no matter how many developers you have, if each one reviews just one other developer’s code, everyone gets a review. (I don’t include the one-developer case in this list because one developer isn’t doing any code review, so they have more time to write code and their output isn’t directly comparable.)

But the linear increase of output doesn’t increase indefinitely. At some point, the amount of useful code added slows down, even to the point of the team being less productive than before the last developer was added. This is a widely-understood phenomenon. What isn’t so widely understood is at what point the slowdown happens; I think it’s far earlier than almost any of us realize.

On Familiarity

This post’s assessment of the slowdown point rests on two major assumptions. Let’s examine them.

- Code quality will make or break a project. It’s not enough to have code that works without bugs or errors. Code that is difficult to understand, fragile, and difficult to change will be a disaster for your project. Over time your delivery of features will be slower, less steady, and buggier. A lot has been written about the importance of code quality, so if you aren’t yet convinced, check out Refactoring, Practical Object-Oriented Design, or Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns. If you still aren’t convinced that code quality matters, there’s no reason to read the rest of this post.

- When you aren’t familiar with the codebase, the code you write is significantly lower quality. Code quality is contextual. You can write a new function that looks great on its own, but if it uses patterns and names different from the rest of the app, duplicates existing functionality, violates assumptions, and can’t easily be integrated into the rest of the app, that’s low-quality code. And it’s not just minor friction: code that doesn’t fit has a snowball effect that majorly increases fragility and slows development over time.

Put these two assumptions together and we can draw a conclusion: familiarity with the codebase will make or break your project.

This conclusion suggests a goal: for every change to the code, we want someone who is familiar with the pre-existing code involved: that is, either writing the code or reviewing it before merge. This will help ensure that every code change is high-quality.

A Fourth Developer Adds Unfamiliar Code

Let’s add a few additional assumptions to further refine the scenario:

- Most of the time developers are modifying or extending existing code, rather than adding totally new code.

- PR reviews are thorough, not just looking for obvious errors or code style, but really understanding the code.

- PR reviews are the main time developers are getting familiar with code. They are not regularly reading through other code to the same level of thoroughness as in PR reviews.

There are a lot of different factors that impact developer familiarity with code. But with these assumptions added, we can pinpoint one specific moment where there is a significant drop in the team’s familiarity with the code. Specifically, the team’s familiarity with the code is significantly hindered at the moment when you add a fourth developer.

How can I make such a specific claim? It’s based on the logistics of being familiar with the code you’re working on. Let’s see why.

When you are a solo developer on a project, you’re familiar with all of the code because you wrote all of it. This means a high level of quality for whatever you’re working on. Now, over time your memory of code fades, so you don’t have perfect familiarity of all the code you’ve ever worked on. For simplicity of analysis, we’ll set aside the impact of memory for most of this post, then bring it back in at the end to account for it.

When you have a team of two developers, each is still familiar with all of the code, because for each chunk of it, you either wrote it or reviewed it. This means you’ll still have a high level of quality in the code you write.

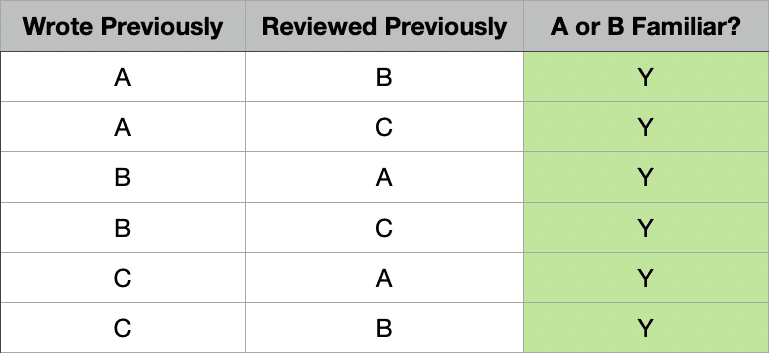

What about a team of three developers? If you think about it, it becomes clear that for every PR of new code, either the author or the reviewer will be familiar with that code. Here’s why we can conclude this:

Call the developer who authored the new PR A, and the reviewer B. Who wrote the code that this new PR is modifying? If A or B wrote that code, then that’s someone in the PR process who is familiar. What about if C wrote that code? If so, then the reviewer of that previous code was either A or B, so that’s still someone involved in the new PR who is familiar.

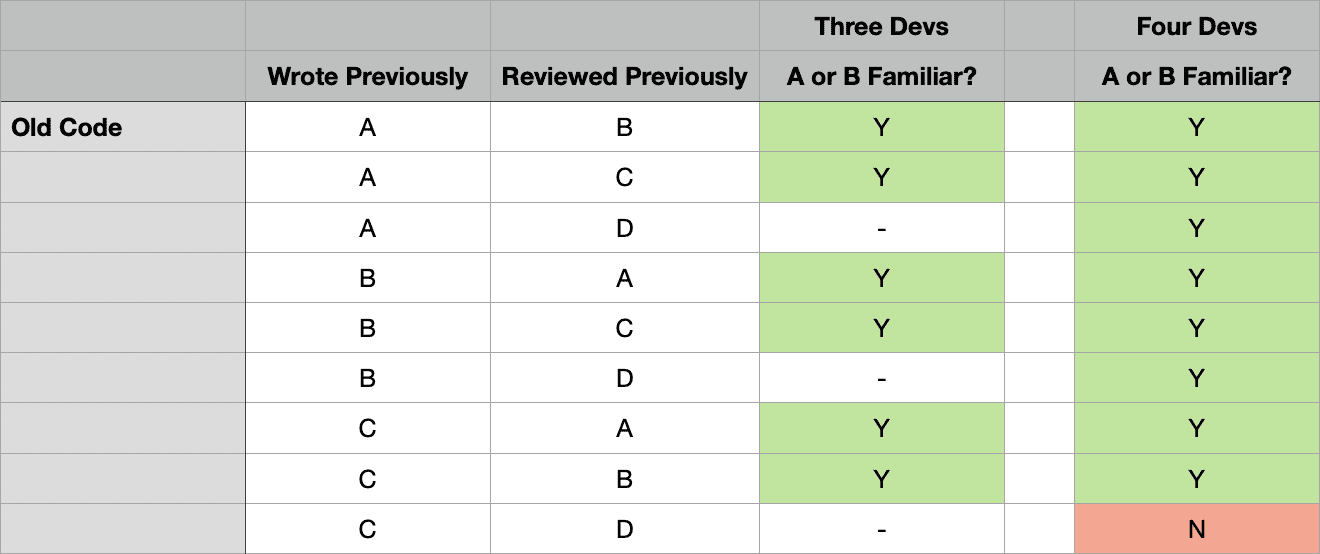

Now, what about four developers? Here things get difficult. Again, call the developer who authored the PR A, and the reviewer B. Is one of them familiar with the pre-existing code?

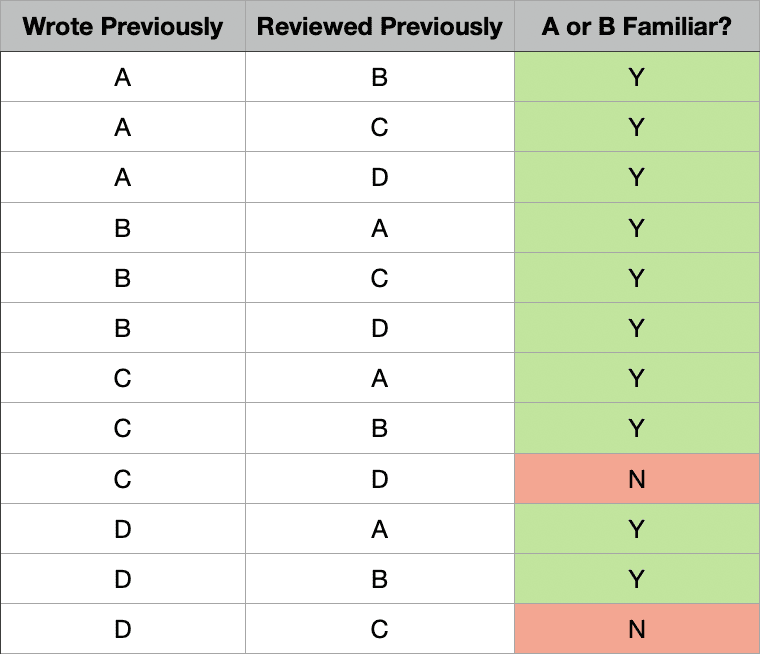

There are 12 possible combinations of who wrote and reviewed this code previously:

In 10 of the 12 cases, either A or B wrote or reviewed the previous code, so someone in this PR is familiar. But in two of the cases, neither is familiar with the code: the case where C wrote it and D reviewed it, and the case where D wrote it and C reviewed it. This is a new situation: now there is a PR that will be merged into the codebase modifying code that neither the author nor the reviewer will be familiar with. This means the quality of that PR will be impacted. Previously, there was no such unfamiliar code; all code was familiar either to the author of the PR or the reviewer. Now, only in 10 of 12 cases, or 83% of the time, will the code be familiar to those involved in the PR.

The Impact of Unfamiliar Code

How big an impact is that loss of familiarity? There are at least three ways to think about it.

The first way to think about the impact is that 83% of the code written going forward will be familiar. 83% is still a fairly high percentage, and you gained the benefit of an additional fourth developer’s worth of output. But on the other hand, with 1, 2, or 3 developers someone in the pair was familiar with 100% of the code written. A sudden drop from 100% to less than 90% is significant.

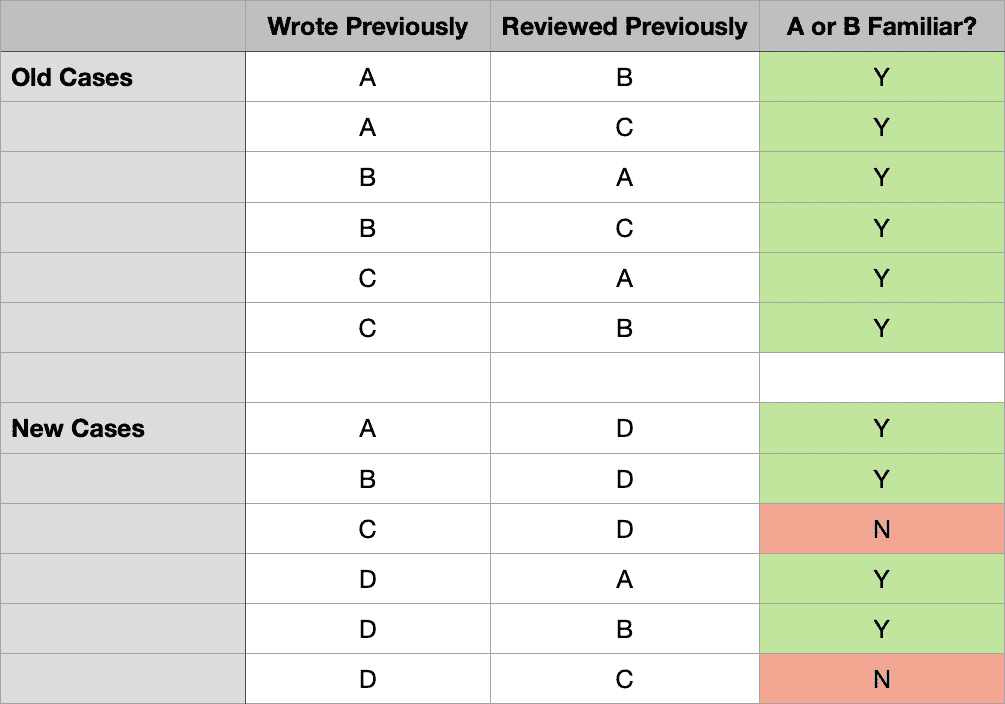

The second way to think about the impact is to focus on the new cases for author/reviewer combinations:

For the six pre-existing cases, there was 100% familiarity. For the six new cases, in four of the six you have familiarity, and in two of the six you don’t. That’s 67% familiarity. That number doesn’t sound quite as good as 83%, but you’re still adding more familiar cases than unfamiliar ones.

But there’s a third way to think about the impact that more directly relates to value delivered, and its picture isn’t good. This is to compare how much familiar and unfamiliar code is written for the three and four developer cases.

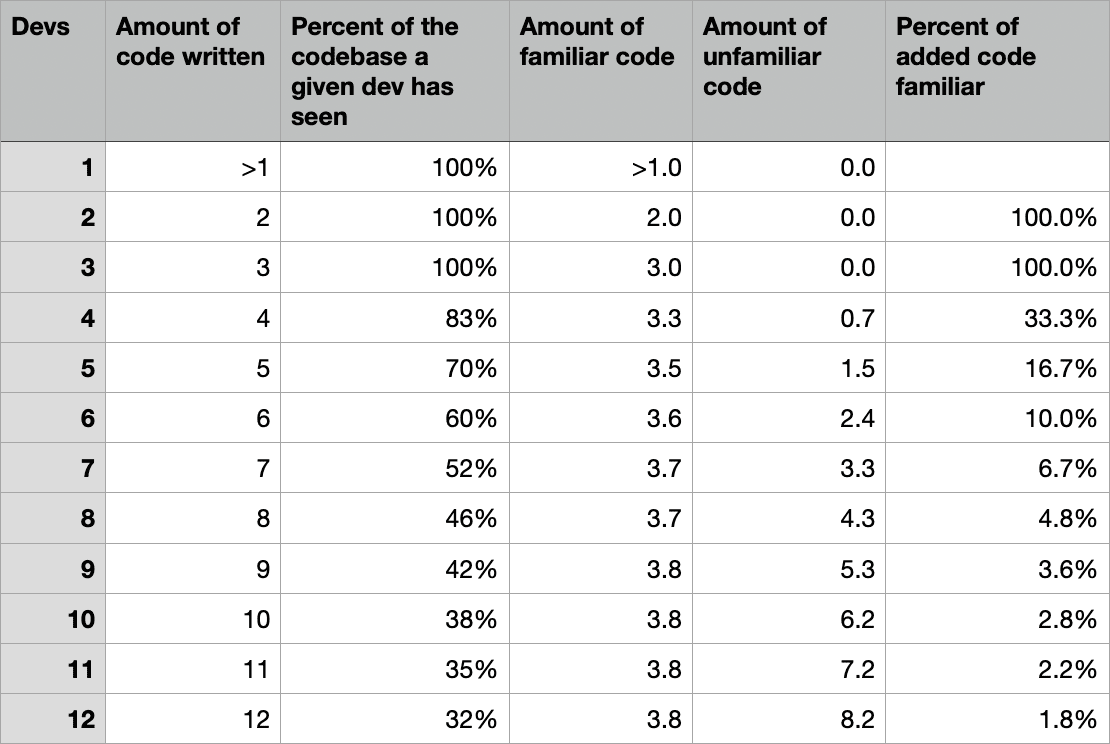

Over a given period of time, we can say that two developers will deliver two units of code, three developers three, four would deliver four, etc. Combine that total amount of code written with the percentage of code understood. With two developers all the code is familiar, so they deliver two units of familiar code. With three developers all the code is still familiar, so they deliver three units of familiar code. But with four developers, only 83% of the code is familiar. So of the four units of code they deliver, 3.33 units are familiar, and 0.67 units are unfamiliar.

Three developers deliver three units of familiar code, and four developers deliver 3.3 units, so 0.33 more. Three developers deliver zero units of unfamiliar code, and four developers deliver 0.67 units. So by adding a fourth developer, you’re adding 0.33 units of familiar code and 0.67 units of unfamiliar code. By adding a fourth developer, for every bit of familiar, well-understood, fits-with-the-system code you add, you’re adding twice as much unfamiliar, less-understood, clutters-up-and-drags-down-the-system code.

The change from three developers to four is drastic. We went from three developers adding no unfamiliar code, to a fourth developer adding twice as much unfamiliar code as familiar. You could say it’s one step forward, two steps back. This is probably very surprising to hear; it was to me.

Is this difference mitigated by the fact that you don’t really have perfect familiarity with all the code in the three-developer case, because familiarity fades over time? No, there is still a major difference. In the three-developer case your only unfamiliarity comes from fading memory, whereas with a fourth developer you’re adding twice as much code that you’ve never seen right from the beginning. Instead of a gradual decay of knowledge, you start out with code you’re completely ignorant of.

How Can This Be?

The drastic change from three to four developers is surprising. If you’re not sure how this math can be correct, let’s think about the cases that lead to it.

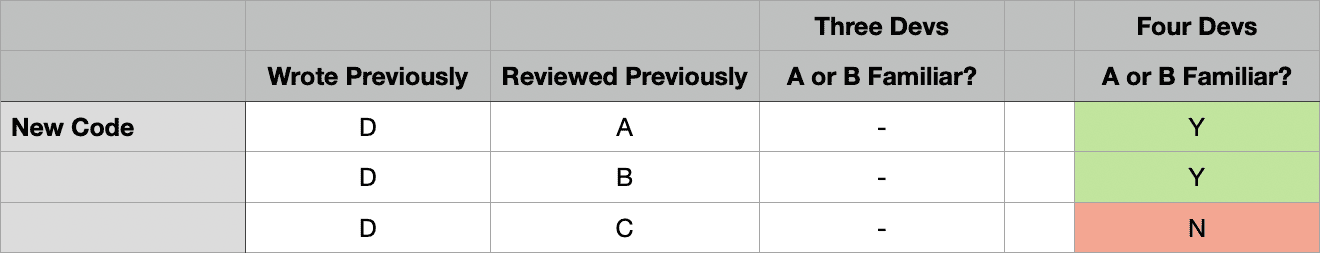

First, let’s look at the new code that D will be writing now that they have joined the team:

We added a fourth developer D who is now writing code that would not have been written before, that A will write a PR to extend in the future, and B will review. 2/3 of the time A or B reviewed that code, so it’s familiar. But 1/3 of the time, when C reviewed D’s code, that the code is unfamiliar.

Next, let’s look at the old code, that A, B, and C would have been writing anyway:

When there were only three developers, all the code that A, B, or C wrote was familiar to A or B. But now, D is in the review rotation for C’s code. So the 1/3 of the time when D reviews C’s code, it is no longer familiar to A or B. So the presence of D on the team disrupts the review process, so that C’s code actually becomes less familiar to A and B than it would have been before.

This is why adding D increases the amount of unfamiliar code more than it increases familiar code. The new code written isn’t always familiar, and now code that would previously have been familiar is less frequently familiar.

To be clear, the problem isn’t the fourth developer added to the project, in and of themselves: we said in the assumptions that all developers have the same skill level and are fully onboarded to the project. D is not “the new developer;” D is just “one of the two developers who isn’t writing or reviewing a given PR.” The blame isn’t on one person; the blame is on the unavoidable dynamics of a four-developer team.

You added a fourth developer to the team because you wanted an increase in the amount of code written, with the implicit assumption that most of that code would be high quality. But your goal hasn’t been achieved. Adding the fourth developer has only increased the amount of familiar code from 3 units to 3.33, and it has introduced the costly dynamic of unfamiliar code, 0.67 units of it.

Digging Deeper

To see how this dynamic continues as a fifth and more developers are added to the project, we can write an equation to describe the different review scenarios and chart it for higher values of team members. As you might expect, things continue to get worse:

The amount of familiar code increases by less and less each time, approaching a hard limit of 4 units no matter how many developers you add. Meanwhile, the amount of unfamiliar code increases linearly. Adding more developers only serves to cause the amount of unfamiliar code to dwarf the amount of familiar code, destroying the quality of your codebase.

A drop in quality is seen far earlier than this, though, and at a precise moment: when you add the fourth developer to the team. All of a sudden, you go from adding a developer who adds all familiar code, to a developer who results in twice as much unfamiliar code as familiar code. If you accept the assumptions of this post that familiarity impacts code quality, then this is not a good tradeoff.

What Do We Do?

What should you do with this information? I can think of two not-so-good responses and two better ones.

First, the not-so-good responses:

- You could reject the premise that unfamiliar code is a problem at all. If it’s okay for an unfamiliar developer to change code and an unfamiliar reviewer to approve it, the problem disappears. But as I argued in the assumptions section, there is extensive writing that warns you against this.

- You could limit PR approval to one or a few developers who have deep knowledge of the system--call them "approvers." If they review every PR, then you've achieved someone knowledgeable involved in every PR. The problem with this approach is that it tends to leave knowledge concentrated in the minds of the approvers, not the whole team. "One knowledgeable person per PR" wasn't the end goal; it assumed that all developers mostly know the system, so that little gaps in knowledge of the current code can be covered by a knowledgeable reviewer. When you plan to have most of your developers uninformed and a higher caste of developers with all the knowledge, your initial PR will be lower quality, resulting in multiple rounds of significant feedback from the approvers, slowing your delivery. It's also dehumanizing to treat some developers as second-class citizens, which is a problem in itself, not to mention the impact on morale and therefore productivity.

Here are the responses I would recommend:

- You could try to make unfamiliar code not so unfamiliar, so the impact of it is limited. One way would be by adopting stringent code conventions. If you’re automatically familiar with many aspects of the code because it’s written in a familiar way, that reduces the chance of misunderstandings and quality problems.

- You could arrange your system so it can be built by teams of three developers max. This may seem impossible, but there are a few different ways: by using high-level abstractions to minimize the code that needs to be written, by focusing on building the most important features one at a time, or by splitting up the system into smaller self-contained pieces.

These two approaches have been discussed at length elsewhere better than they could be summarized here. But the surprising thing may be how early you need to reach for those approaches. They aren’t for when your team has reached a dozen developers. There is a specific impact of team growth on code familiarity at a precise moment: when you add a fourth developer. And even if your team is three or fewer developers now, if there is a chance you’ll add a fourth developer in the future, the code you’re writing now is what you’ll be building on. If you take the code-familiarity problem seriously now and mitigate it, you’ll be ready for if and when you add the fourth developer–or you may find that you don’t need them after all.

One final note about pairing. At the start of this post I included the assumption “Developers create a feature branch working solo, then open a PR.” There’s an alternative to that assumption: you could make pairing a regular practice on your team. With full-time pairing (standard in Extreme Programming), every bit of code you write will have two developers familiar with it—probably even more familiar than if one of the developers only reviewed the code. Even if not full-time pairing, if you make it a regular practice to pair, that will have some effect on team familiarity with the code. I haven’t worked extensively with either of these approaches, so I can’t speak to how the math in this article works out differently in those cases, not to mention other pros and cons of that approach. But erring on the side of increasing developer familiarity with the code will tend to have a positive effect.

Thanks to Bryan Lindsey, Jeremy Sherman, Nate Sottek, Ron Jeffries, and Eve Ragins for review and input.