Thanks to hachi8833 for translating this post into Japanese.

The blog post “Better typing in Ruby” by Brandur Leach describes the situation at Stripe from which their Sorbet static type checker emerged, as well as the benefits it provides to them. In doing so, it brought up a number of points that I’ve seen in the past that cause me to have a moderate view of the benefits of static typing. The post mentions problems in the Stripe codebase that static type checking helps to mitigate. But static types don’t solve those issues; their continued existence is likely to cause other costs.

Now, I don’t mean to say that Stripe made a mistake or should have done something differently. I haven’t worked in a Ruby codebase of nearly the size of theirs, only much smaller ones, so I’m in no position to evaluate their decision. It could very well be that in their context the problems are unavoidable and static type checking is the best that can be done to solve them.

Instead, I’d like to use the blog post as a jumping-off point to think about the problems it describes in the abstract, and how I would approach those problems if they occurred on a project I was on. Static typing is not the first solution I would reach for as the way to solve them.

With that, let’s look at the problems.

Static Typing Applied to Problems

Ruby does a poor job of encouraging modularity, so the code had ended up as one giant amorphous blob, with everything calling into everything else, and all boundaries purely theoretical in nature.

This is really a statement of cause-and-effect: because “Ruby does a poor job of encouraging modularity,” therefore “the code had ended up as one giant amorphous blob.” But is the cause of an amorphous blob of code really the language itself?

Ruby doesn’t write code; developers write code. If Ruby doesn’t have facilities that encourage modularity, it’s still developers who decide whether to write code with “everything calling into everything else”. The effect of the language is how strongly it encourages you in one direction. You might say, because Ruby doesn’t have facilities that strongly encourage modularity, the developers needed to be more careful to write in a modular way, and they were not careful to do so.

…most of the time engineers were modifying existing code rather than writing it anew. Examining any section of it, all you had to go by in figuring out the type of anything was naming…If no type was readily apparent, the best thing you could do is throw a Pry statement into the path, try to find a test case that exercised it, and inspect variables at runtime…

…Code is analyzed whether it was tested or not, so we have an extra layer of protection even where there are holes in the test coverage.

When you have a significant amount of code that isn’t tested, that’s worrying. I don’t ascribe to 100% test coverage, but what I don’t test is mostly my integration/adapter layer to external systems and libraries. For the code that is my application, I want it thoroughly covered by tests.

Here we’re talking about the process of “modifying existing code”, but we aren’t sure if or where there is a test that covers this code. If that’s the case, knowing the type of a variable isn’t enough assurance for me: I want to make sure my changes don’t break the business logic, so I need that code to be under test.

…try to find a test case that exercised it, and inspect variables at runtime. This was an excruciatingly slow process (Ruby’s interpreted, so more code means more startup overhead)…

…Static analysis was faster to run than a single suite (i.e. one file) of tests, and often faster than even a single test case (our tests have significant startup overhead).

In Ruby, slow tests are generally not slow because of interpretation per se, but rather because they boot up the whole framework. Rather than writing tests that boot up the framework, it’s best to write unit tests that exercise objects that have no dependency on the framework or any other external objects. In such tests, you aren’t booting up a framework, and the amount of code you’re interpreting is minimal anyway.

The original author might’ve intended for a variable to be one type, but it may have subsequently picked up new uses and had its interface broadened to include many possible types…

…Although it may have originally been intended for use with integers, at some point someone notices that it works with strings as well, and starts passing those in too.

It’s important for the developers on a codebase to understand how that code is being used. It’s true that the way chunks of code are used changes over the lifetime of that code—this reusability is a big benefit. When this happens, it’s important to disseminate that knowledge so others using the code are aware. On a large codebase, you can’t review every PR or keep every bit of the application in your head at once. You need other ways to communicate the use of a bit of code. Testing inputs is one way to do this that has the benefit of being executable.

The author does mention tests of input types, but I don’t quite follow his point. Yes, if you want to change a method and tests show that your change doesn’t handle all input types then you will need to account for that. That’s not all that different from the constraints types put on the method. If a method is used for multiple types then it needs to be written to support them—a lack of static types doesn’t increase the effort needed here.

Developers would make an incorrect assumption while changing something, have enough success in the test suite that it reported no failures, only to find 500s thrown in production on an untested path (we write a lot of tests so in theory there shouldn’t be too many of those, but actually, there’s a lot).

If your testing strategy isn’t covering most paths through the code, that’s a scary place to be—whether or not you have static types. It’s important to know that your business logic works on each of those paths, and static types can’t tell you that.

The strategy I use for thorough test coverage is to use unit and acceptance/system tests together for their strengths to cover each other’s weaknesses:

- Unit tests thoroughly exercise each class so that its behavior is well-specified, including covering every code path.

- Acceptance tests exercise the whole application together so that we know those units work together.

Acceptance tests can’t cover every combination of paths because the cost is exorbitant. Instead, you design them in such a way that, given the guarantees the unit tests provide, the acceptance tests cover what is needed. For a large application, you can’t run all the acceptance tests on every change, but they can and should certainly be run before every release. I can say from experience that this won’t catch every possible error, but it should be the vast majority.

And while static analysis is great, we shouldn’t forget that type signatures are for people too. Being able to see what the expected types of any particular variable or method while reading code is a huge boon for comprehension. Sure, a great IDE can help with this too, but why not both? It’s free.

This section not only describes the benefits of type signatures without mentioning downsides, it explicitly says that they are “free”, implying that there are no downsides. And there a number of folks today who argue that explicitly. But many others argue for the benefits of dynamic languages, asserting that there are tradeoffs. What are they?

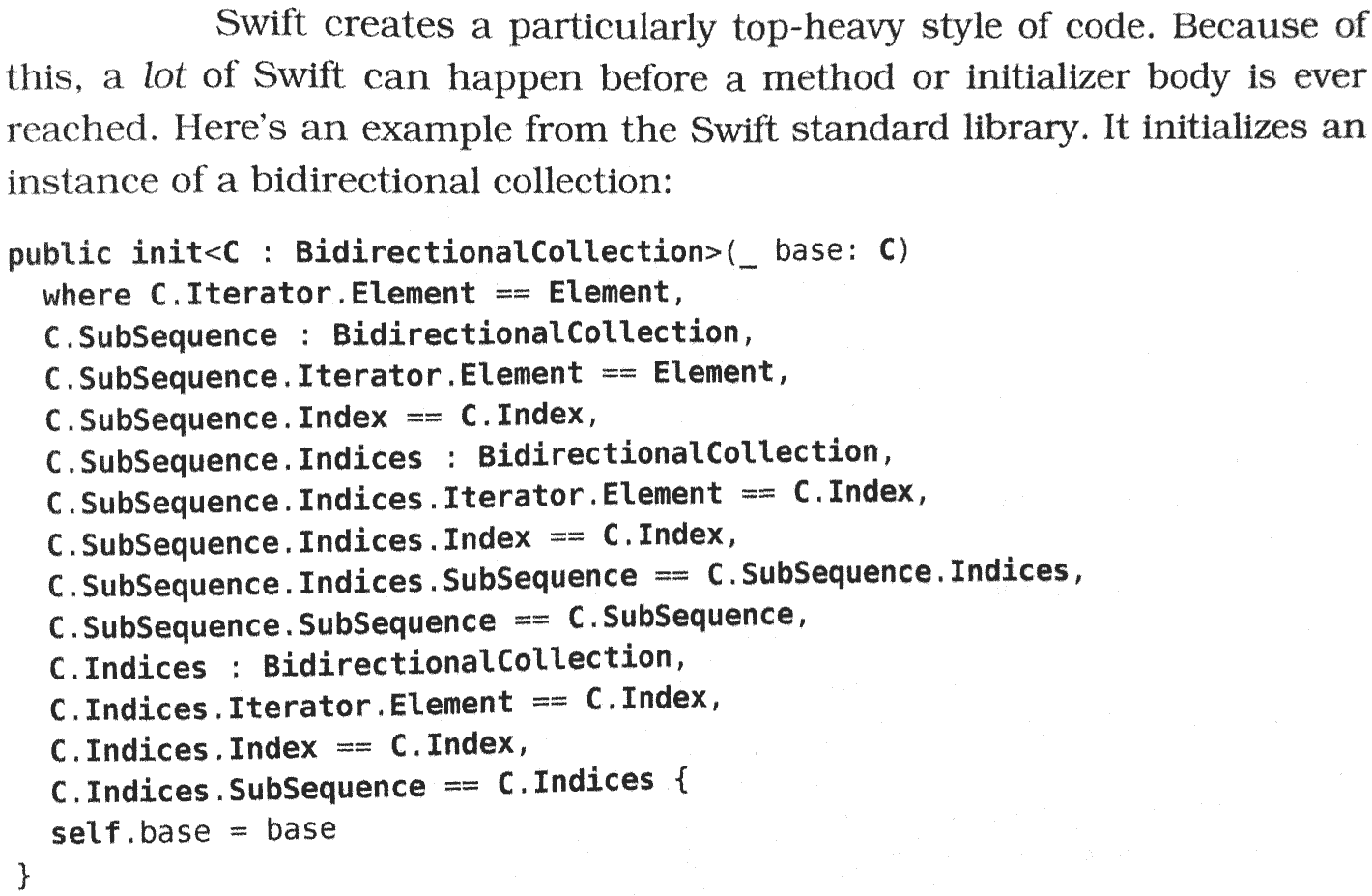

In an extreme case, complex type signatures clutter up code so much that the overwhelm the logic itself. Take this example written in the Swift language from the book Swift Style:

It may not be obvious, but the only application code here is self.base = base; the rest is an incredibly complex type signature.

Even in more typical cases where the type annotations are simple, the type annotations still clutter up the code. One of my favorite things about Ruby is how clean its syntax is, allowing the business logic to be front and center. By contrast, languages with type annotations clutter up the code with information that is obvious to me most of the time. Matz stated a similar point in his RubyConf 2019 keynote when he described why Ruby wouldn’t add type annotations but instead put them in separate files: he said that type signatures aren’t DRY, and so by keeping them out of your Ruby code it retains its DRY nature.

And that duplication has a cost: every time you’re reading code your brain has to process the type signatures and, in cases where the types were already obvious, that is effort for no benefit. Even if it’s only a small amount of effort, it adds up over time.

When is Static Typing Helpful?

From the above quotes, a picture emerges of when static typing provides the most benefit:

Static typing is helpful when you’ve written an application with poor modularity. But it’s best not to write an application with poor modularity at all, and even with static typing, poor modularity will cause problems. Now, I don’t have experience writing a large monolith with a large team and maintaining good modularity, so that may very well be difficult to do. But the closer you can get, the better, and it seems like with good training of new developers and thorough code review, you should be able to make strides.

Static typing is helpful when you haven’t consistently covered your code with tests. For code that isn’t tested, it’s hard to see what it’s doing, and it’s hard to know if a change you make is safe. Static typing can help with that. But even with static typing, testing your code is important. Individual units of code should be tested, and overall user flows through the application should be tested as well. Tests are even more important in a dynamically-typed language, which is why testing has been emphasized in Ruby. In most type systems (with the possible exception of ones like Idris, which I haven’t used), static typing can’t guarantee your business logic is correct, so you need those tests. No matter how large your codebase and your team, it is reasonable to require tests for most code. Whether you use thorough code review (my preference) or code coverage metrics (which have significant problems but may be better than nothing when you don’t do thorough code review), you should be able to ensure that most of your code has tests.

Static typing is helpful when you’ve written slow tests. This is why there has been a push for fast tests for some time in the Ruby community. There are some workarounds to speed up integration tests, but the most reliable approach is to write plain old Ruby objects that don’t use a framework along with true unit tests that tests those objects in isolation. This takes discipline, and the need for it is not apparent at first. But because even with static typing you need to confirm your business logic works, fast tests are important either way.

Static typing is helpful when you don’t understand how your code is being used. When code is written for one purpose and then used outside of that scenario, your code is now used in ways you don’t understand. But it’s important to gain understanding of how your code is used. Even if the types line up, having your code used in ways you don’t understand can still result in bugs and increased maintenance cost. You want to understand your code, so that at any point in time you know what it’s used for. If the use of some code changes, then your understanding of it needs to change as well. That understanding can be disseminated via adding tests to cover the new cases (for example, using #add not only for integers but also for strings), renaming methods and classes to reflect the broader scope, and updating documentation. This is a disciplined approach to evolving your application. Static typing is a way to enforce that you do this and catch if you forget, but, as mentioned above, they add cognitive overhead, and can’t catch cases where the types are the same but the business use of the code has differed.

So, in summary, static typing is especially helpful in codebases you don’t understand with poor modularity, with incomplete and slow tests. If you find yourself in that situation, static typing will probably help.

A Better Solution

But even with static typing, it is still not a good situation to be in a codebase you don’t understand with poor modularity, with incomplete and slow tests. You want to be in a codebase you understand with good modularity, with thorough and fast tests. And if you have that, the value of static typing decreases significantly, and their costs to readability increase.

I’ll say one last time that I haven’t worked in a very large Ruby codebase with a very large team, so I can’t say how difficult it is to keep a codebase in the ideal state I mentioned above. There is a lot of industry wisdom that static typing helps in that circumstance—though I’m not always sure whether those who say so agree about the benefits of dynamic typing. Maybe if you’re pursuing understanding, modularity, and thorough and fast tests, static typing is a helpful guardrail at a certain size.

But for smaller projects with smaller teams, I know from experience that deeply understanding the codebase, modularity, and thorough and fast tests are very possible. Go after that, because you want it whether you use static or dynamic typing. And if you have it, and you love the way Ruby looks and works, you may not have any need for static typing.